In our two previous blog installments, we have explored the rich yet often inequitable history of the architecture of Cape Town. However, our journey is not yet at an end. After the injustices of Apartheid and the effect it had on the city’s architecture, South African architects were left with the difficult task of rebuilding the built environment for a better future and attempting to resolve some of the issues of the past.

Coinciding with the emergence of democracy in South Africa was the birth of a new architectural language –

contemporary

. Much like modernism – contemporary buildings were universal and quickly became a ubiquitous feature of Cape Town. They were, in a sense, divorced from any cultural history, a blank slate and chance to start again – much like the first democratic election. The new architectural style would inevitably be adopted by the wealthy traditionally white residential areas of Cape Town first, but would it fall prey to the same fate as Modernism – is inextricably linked to the inequality of Cape Town – or could the new architectural language be employed in the public spaces of the city and used to unite South Africans with the promise of a new and exciting future.

Changes to the Atlantic Seaboard

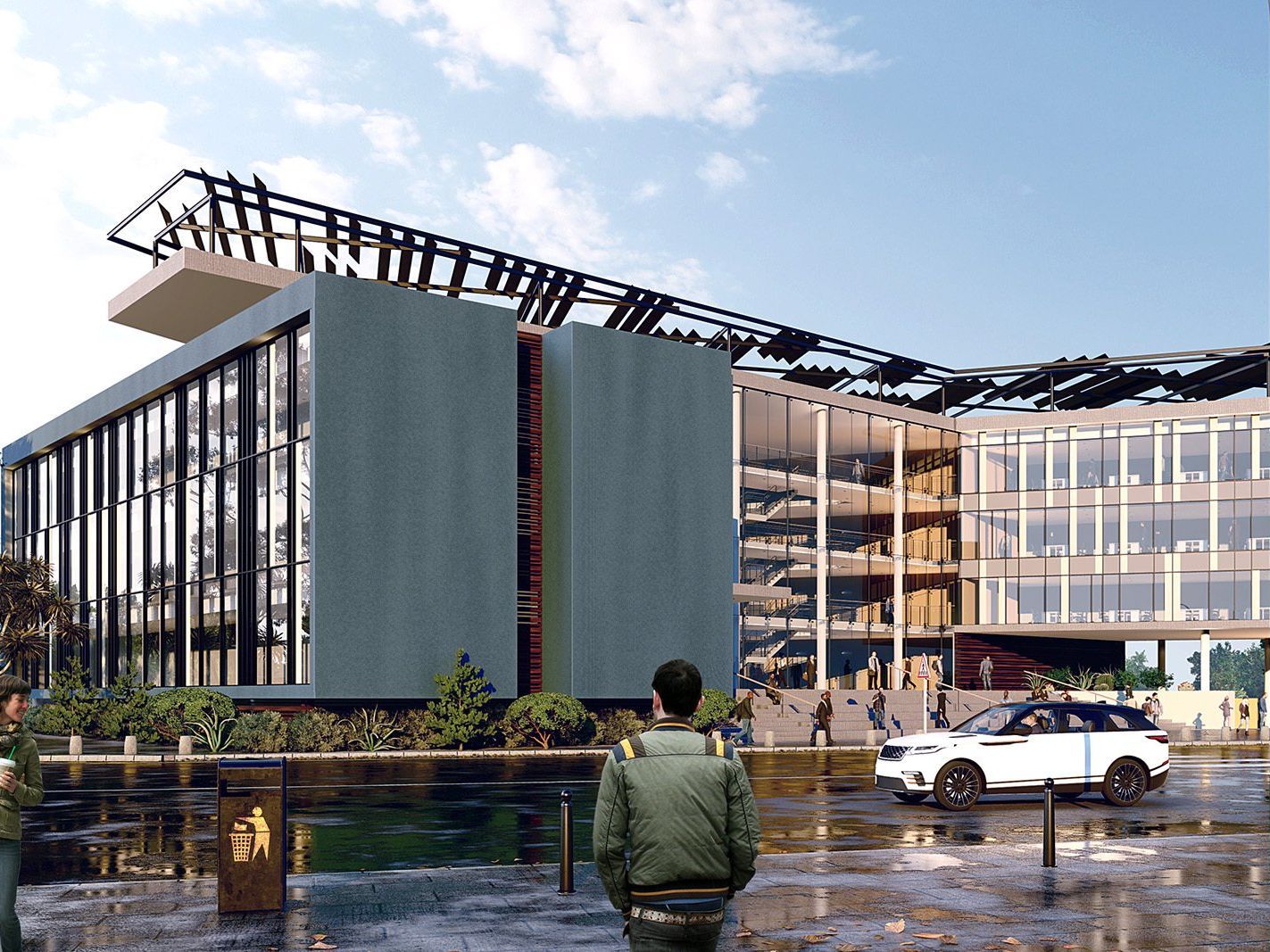

One of the broadest areas to see the rise of contemporary architecture in Cape Town was the Atlantic seaboard. It would seem that ocean views have always been synonymous with the geometric forms and openings of contemporary architecture – not to mention the property value of these areas. Since the very beginning of the contemporary wave, firms such as DesignScape architects have been working hard to produce sustainable, inclusive, and contemporary buildings that remain sensitive to the opportunities and restrictions of the seaboard’s context. Robert Silke of Louis Karol Architects, one of Cape Town’s most prominent firms, shed some insight on the ups and downs of the Atlantic Seaboard, and in particular, Sea Point, where a significant amount of regeneration has taken place over recent years.

Pippa Hudson of Cape Talk spoke to Silke in 2014 about the matter. According to Hudson, during the late 1990s and early 2000s, an overwhelming number of businesses in and around Sea Point closed shop and fled, leaving the area resembling a shell of what it had been decades before. Silke had an active role in the area’s impressive regeneration to the bustling location it is today.

Silke had an association with Sea Point for the duration of his childhood, and he explained that towards the end of the 1980s, Sea Point – like any other traditionally white area – was the first-world Riviera and everyone wanted a part of it, injustices and prejudices evident as ever. Many apartments in the area were constructed with the housing of their domestic workers in mind, meaning that there were separate quarters for them. As the Group Areas Act started to fall apart, there was radical social change occurring in Sea Point. It was one place in Cape Town that was most open to social change, said Silke. As a result, it transformed very fast, and all transformations – whether positive or negative – are traumatic, he added.

Then of course came the capital flight from established urban centres. The advent of the shopping mall, and in particular developments in the V&A Waterfront led to many restaurants and companies packing up shop and moving. In Silke and his firm’s involvement in various projects in the area years later, they made resounding ripples in the direction of the suburb. Silke himself stated that there was a goal to make Sea Point bigger than just the sum of its parts. Anyone taking the time to visit the seaboard today can see how tangible this goal has come to be.

Designing for a better, and more diverse future

In a country still tainted and deeply affected by the injustices of the past – and present – the importance of diversity in the architecture industry cannot be understated. For architecture, and especially urban design, there must be discourse about who gets to design particular spaces, and why. All around the world, in recent years, city planners have grappled with how to design and build spaces that can better serve people who have traditionally been left out of design. Buildings are just as important to the equation as spaces, a sentiment made clear by Althea Peacock, one founder of Lemmon Pebble Architects located in Johannesburg. Lemon Pebble is one of South Africa’s only architecture firms run wholly by women of colour.

As reported by The Christian Science Monitor in 2021, Peacock states that female architects often design buildings that are “more empathetic to the ways in which women are vulnerable.” This can mean anything from considerations of more bathrooms, places to breastfeed or simply more lights to make vulnerable occupants feel safer. In our country, alterations such as creating more space on sidewalks for hawkers to make their living is another relevant example. In an industry that is hopefully more considerate of encouraging diversity, there is no telling the exciting developments that the future holds.

The future is sustainable

Like the rest of the world, the construction industry is changing. At the centre of this change is a significant shift towards more sustainable architecture. For architects, this means carefully observing the design of new structures with a different perspective, one that involves a focus on increasing energy efficiency, cutting back on carbon emissions, putting renewable energy to work as well as meticulously choosing building materials that won’t make a negative impact on the environment. Essentially, sustainable architecture signifies any building project that strives to have next to no environmental impact.

This approach requires certain design methods, energy-saving techniques as well as materials in both the design and development phases in a building with the goal of preserving the surrounding communities, natural resources, and nearby ecosystems. In this way, the built environment is to become integrated into the natural one. However, sustainable architecture does not only take into consideration the design, building, and construction legs of the journey. Rather, it also carefully anticipates the maintenance and operational requirements that have to do with the life cycle of the building.

This is vital, since ensuring sustainable development and making sure that the building sports conservation for as long as it is in existence is key in practicing sustainable architecture. In many ways, sustainable architecture is likened to green building principles, since both practices share several elements, namely a focus on reducing carbon emissions, buckling down on energy consumption as well as bettering water efficiency. The two also place great importance on augmenting the comfort of the building’s occupants.

When encountering most kinds of buildings, there are a number of varying characteristics that are indicative of sustainable building practices. These characteristics can be categorised into main aspects or considerations, including:

1. Effective Use of Space

Architects who specialise in sustainable design tend to seek out ways to shape the environment around their needs, by looking at elements such as where the sun rises and sets in relation to a potential building design – or how it will behave during different seasons, manners in which natural light can be enhanced, or simply how to mix energy-saving practices into the equation. Using space effectively is one of the most essential practices to be carried forward in the future of architecture, and one of the pillars of sustainable design.

If it is done correctly, the building in question should boast efficient temperature control, ample indoor airflow and ventilation as well as appropriate natural lighting. These preferences can be easily achieved with today's design tools.

2. The Prioritisation of Energy and Resource Efficiency

Placing resource and energy efficiency at the forefront of design is another important aspect of sustainable architecture. Doing so often involves making use of natural and sustainable energy sources. Oftentimes, renewable energy applications such as solar, geothermal and wind are used.

3. The Use of Environmentally-savvy Building Materials

Last, but certainly not least, the use of non-harmful building materials is considered by many to be the pinnacle of sustainable architecture. This practice usually involves using eco-friendly or recycled materials in building projects where at all possible. This can also be interpreted into the usage of ethically-sourced or local materials such as stone, wood and aluminium. The overarching idea is that these materials would not have travelled far, and thus caused less carbon emission. Local communities would also have been supported.

A great number of sustainable architects have followed through by turning to modern design trends. These involve using features such as large glass planes to invite in more natural light, the use of green rooftops, as well as installing aluminium shutters that are known to both absorb UV rays as well as assist with indoor temperature control. On the matter of green rooftops, The Cape Town Management of Urban Stormwater Impacts Policy of 2009 advised for the implementation of green rooftops – defined as design practices that “encourage biodiversity, amenity and aesthetics.”

A few years later in 2012, the City also published The Cape Town Smart Building Handbook , which showcased a pilot garden roof as a leading example. However, despite these efforts, many argue that Cape Town is behind some of South Africa’s other major cities when it comes to the green rooftop scene. Another interesting suggestion was that of the implementation of “green walls” in and around informal settlements, in order to promote a better quality of life. There is much opportunity and only time will tell if more of these green design practices will sprout in and around the city.

However, do not be fooled into thinking that Cape Town is behind when it comes to general sustainable architecture. One project, executed in Bishops Court, named House Burnett Prinsloo, was acclaimed in the 2017/2018 Afrisam-SAIA Award for Sustainable Architecture. This is but one example but is worthy of further explanation. As reported by the CapeTown ETC blog, the awards focus on environmentally-conscious infrastructure and design.

Robert de Jager architects were responsible for the design of House Burnett Prinsloo, the project receiving praise for its achievement of balance between the contrast of concrete and nature. Across the city, budding and seasoned architects alike are looking for more sustainable practices to enhance their work and ensure that the design and project footprints they leave behind are positive ones.

Final thoughts

The history of Cape Town’s architecture is a long and complex one, brightly decorated by innovations of the past but also blighted by its injustices. There is no telling what the future may hold, but what we do know is that with the high standard of architecture firms dotted all around the Cape at the helm of sustainable and modern design, perhaps better informed by the knowledge of the past and its mistakes, have a new story to tell.

For more information about our innovative architectural services and on how we can assist you, get in touch with our team of professional architects and designers in Durban and Cape Town.

Cape Town

109 Waterkant Street

De Waterkant Cape Town

South Africa, 8001

Durban

Rydall Vale Office Park

Rydall Vale Crescent

Block 3 Suite 3

Umhlanga, 4019

Website design by Archmark