In the previous installment of this blog, we left off discussing the impact of Sir Herbert Baker’s building designs on the overall architectural identity of Cape Town in the early 20th century. These designs, of course, represent the early stages of the development of a totalitarian architecture – which would eventually serve to further promote ethnic segregation during Apartheid. The architecture of Cape Town is incredibly layered and multi-faceted. Cape Town, despite its shining beauty, has a long dark history – and these roots significantly influenced the architectural development of the city. This series of blog posts seeks to further explore exactly how Cape Town’s architecture came to be, and how we might rebuild for a better future.

The Art Deco period

Developing parallel to Baker’s revivalist Cape Dutch architecture, was Cape Town’s own Art Deco movement – beginning around 1918 and coming to end just before the second half of the century. Art Deco (also known as style moderne ) is an architectural movement that developed in France during the 1920s, immediately after the First World War. It was first showcased at the centre of the design world – Paris – at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, and from there it developed into a major architectural style wielded throughout the western world.

Art Deco presented a drastically new architectural language. Unnecessary decorative elements and ornamentation were stripped away and replaced with clean lines and symmetrical, geometric patterns. This responded to the new forms adopted by transport systems and other technological advances that were implemented in an attempt to increase efficiency. Art Deco represented a massive paradigm shift in the way architects saw the future of the built environment.

The movement made its way to Cape Town in the 1930s. The style was disruptive and at odds with the prevailing – and extremely conservative – architectural movement characterised by hierarchical spacial divisions. Instead, Art Deco architects were taking inspiration from other countries and worldly developments. Across the city – apartment blocks, office buildings, cinemas, and even petrol stations were adopting the new style.

Greenmarket Square is a great example of Cape Town’s Art Deco architecture. When observing the buildings surrounding the public square, one can see the clear objection architects faced to the development of an Art Deco aesthetic throughout the city. In many of the residential buildings, the Art Deco designs are muddled with a classical, Edwardian architectural language. This clearly demonstrates how architects at the time were trying to find a compromise between the architecture of the old world, and the architecture of the future. This was certainly made more difficult by the pressures of the radically conservative sociopolitical landscape at the time.

These attempts to modernise the city did not sit well with architect Herbert Baker, who very much represented the antithesis of what Art Deco stood for. Much like his older colleagues,

Baker believed that the modernist school of thought should be rejected, and clearly advocated for tradition and nostalgic value in architecture – even at the expense of progress. This illustrates the massive hurdles Art Deco was up against, as well as the wall it was attempting to break down in the process. Unfortunately, the worldly developments, societal progress of other countries, and architectural paradigm shift would not win the fight against the ever-growing authoritarian regime in South Africa just yet.

The development of authoritarian architecture in South Africa

The Cape-Dutch style laid the foundation for the weaponisation of architecture during the darkest period of South African history, with it’s racist hierarchical spatial divisions inherent in every design. From the urban planning of the city to almost every new building designed during apartheid, the architecture of Cape Town at this time was designed to divide and conquer.

Dividing spaces into racial categories became commonplace for architects as a functional planning challenge. These buildings bore no overtly racist symbols (with the exception of the old South African flag in cases) – but rather, observing building plans will reveal a deeper, more covert form of racism and segregation. The ideologies of Apartheid were cemented into the country’s buildings and strongly ingrained into its architecture. To many architects operating in this systemically racist context, discrimination was compartmentalised – and ultimately became a completely nonchalant practice.

At an urban scale, city planning in Cape Town also segregated communities along racial lines. These plans ensured that black township communities were completely devoid of any economic opportunity. These townships were designed to include incredibly small homes which were situated at least 40 kilometres away from the city – forcing black South Africans to spend the majority of their income commuting, and rendering community development almost impossible. Unfortunately, this is still the reality for many South Africans today.

The Group Areas Act

The most obvious example of this ingrained discrimination was the Group Areas Act. On 27 April 1950, the Apartheid government passed the Act, which enforced the segregation of the different ethnic groups to specific residential and business sections in urban areas, following a system of urban Apartheid. Of course, areas allocated for people of colour were designed to socially and economically oppress. The architecture of these areas was extremely utilitarian – designed to be as inexpensive as possible to construct, with no spatial provisions for socialising, recreation, or economic opportunity. They are incredibly hostile structures, with their primary function of ethnic separation being clear in their architectural expression. This is best observed in the design of hostels throughout South Africa. Hostels were buildings designed for complete control over their occupants.

Hostel Architecture

As a result of Apartheid, hostels can be found all over the South African landscape. The buildings were architecturally similar to prisons, in that their plan layout was designed to both isolate and dehumanise. Originally built to house black labourers working in the mines, hostels were designed to enforce complete control – stripping the labourers of their identity outside of their work. They were created to handle a large influx of black labourers who weren’t allowed to live in the city. The city had the best interests of white South Africans at heart, and therefore black labourers could only work there with a permit. They could not occupy the space outside of work hours, let alone live in the city. The hostels were therefore designed to maximise the amount of black labourers occupying the space – meaning families were not allowed to visit or live with them.

The ideal architecture of containment required design at the hands of white authorities working in the mining sector. The hostels had to take the form of robust buildings with carefully controlled entrance and exit points. The buildings needed to be strategically located near places of authoritarian power, such as mine security or the police, but still far enough from white areas to remain invisible and promote compartmentalisation.

Modernism during Apartheid

Despite Modernism’s objective of departing from conservative traditions and classicism, the Modern architecture produced in South Africa in the late 20th century will always be inextricably linked to Apartheid. Unfortunately, the Modernist designs of architects such as Roelof Uytenbogaardt will always carry the weight of South Africa’s dark past. Buildings such as the Werdmuller Centre – a once-elite shopping mall in Claremont – were designed exclusively for the white population of Cape Town. This begs a difficult question for Cape Town Architects practicing today: How can a building with this history be honestly and convincingly repurposed for the future?

Apartheid worked directly through the design of public spaces – using the Modernist movement to produce spaces of inequality and separation. Architects applied themselves to design clean, geometric forms with a Modern material. Ultimately, however, these forms would only be used to further segregate the people of South Africa and oppress people of colour.

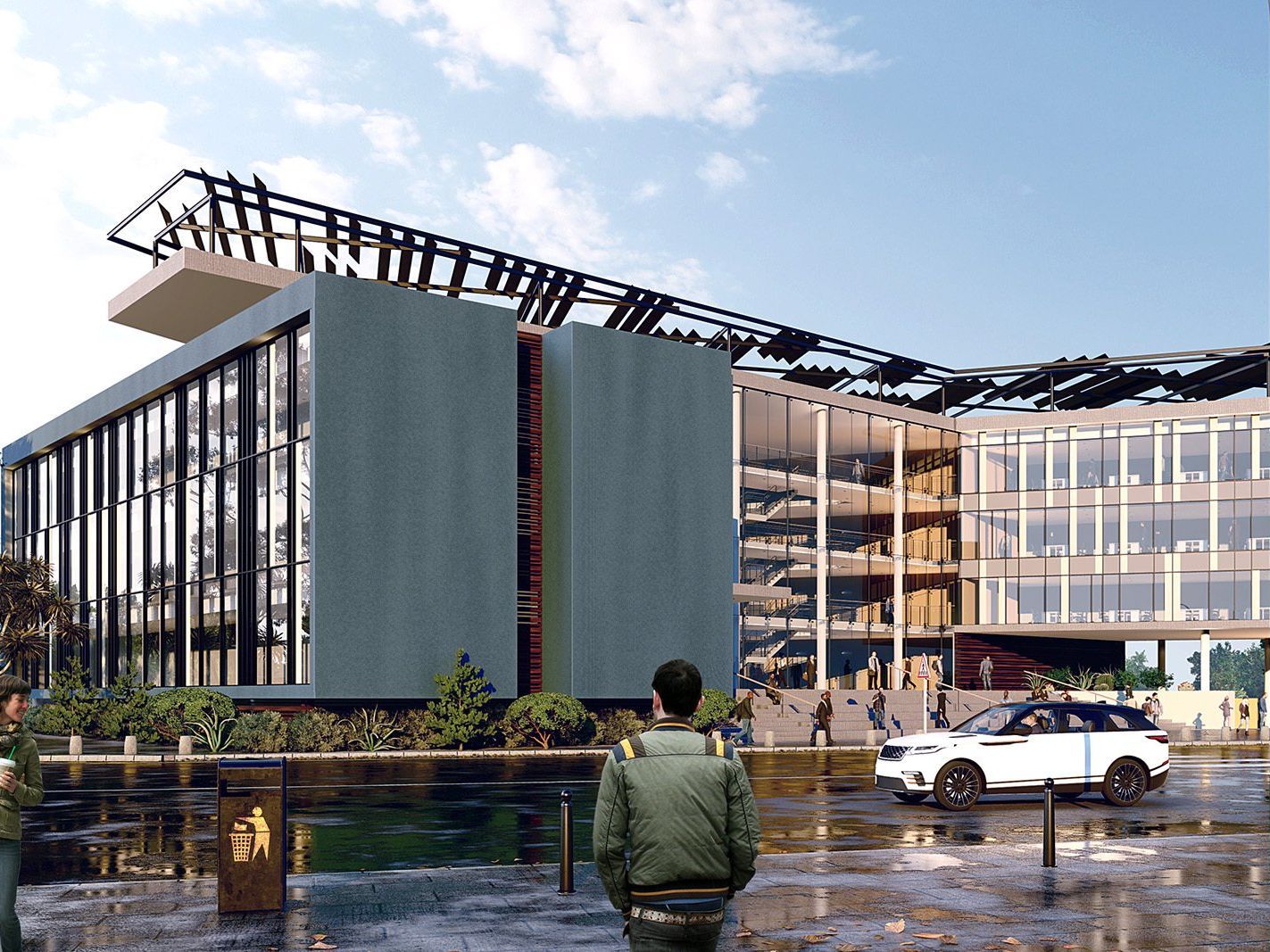

Modernist buildings can be found everywhere throughout Cape Town, but most notably in wealthy, ‘traditionally white’ residential areas. These buildings are typically modern, in that they

employ a level of horizontality – often responding to the mountainous slopes of these areas – clean white facades, floor-to-ceiling glazing which offers views of the South African landscape, ribbon windows framing more selective views throughout the house, cantilevering balconies and terraces, as well as geometric landscaping. These buildings certainly have architectural merit – and one can definitely appreciate their overall contribution to South African architecture – but if their designs are to be accurately analysed, they must be analysed in the context of the social crisis that was Apartheid.

An enduring legacy

Today, the effects of Apartheid can still be felt in many areas of South African life. If modernist buildings designed towards the end of the 20th century could not escape the far-reaching arm of the Apartheid government, what can we do to ensure today’s architecture does not succumb to the same fate? What can architects do differently to make sure the built environment they design improves the lives of all South Africans, and promises a future of equity and inclusion? Is contemporary design the answer?

Look out for the third installment of this blog, in which we’ll delve into even more topics in our journey to investigate the architecture of Cape Town.

For more information about our innovative architectural services and on how we can assist you, get in touch with our team of professional architects and designers in Durban and Cape Town.

Cape Town

109 Waterkant Street

De Waterkant Cape Town

South Africa, 8001

Durban

Rydall Vale Office Park

Rydall Vale Crescent

Block 3 Suite 3

Umhlanga, 4019

Website design by Archmark